We work with the nematode worm C. elegans that is maintained in the lab by growing it on a lawn of bacteria: a benign strain of E. coli. My interest in folates started when we made the serendipitous discovery that we could extend the lifespan of the worm by inhibiting folate production in E. coli. Interestingly, lifespan extension is not a result of decreasing folate supply to the worm. Instead, preventing bacterial folate production changes bacterial behaviour or metabolism in a way that is beneficial to the animal.

My interest in folates started when we made the serendipitous discovery that we could extend the lifespan of the worm by inhibiting folate production in E. coli

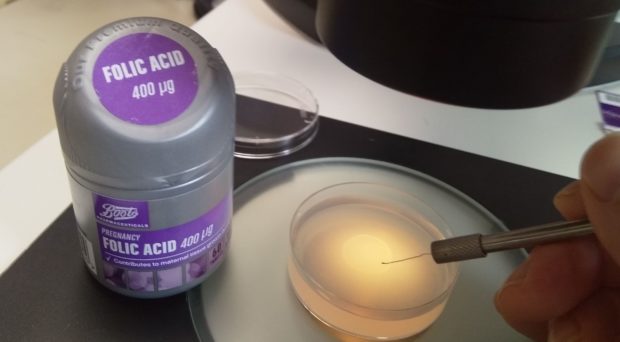

The worm gets its folate from E. coli but it needs very little: we found that even when bacterial folate is decreased dramatically, the worm grows normally. In fact to see something that resembled a developmental defect, we had to use a specific C. elegans mutant AND bacteria with low folate. This folate deficiency could be prevented easily by adding folinic acid, a folate found in nature, but folic acid was much less efficient. In this paper, we show that folic acid requires a route through E. coli to prevent the developmental defect.

This result was unexpected because E. coli cannot take up folic acid. However, it can take up a breakdown product of folic acid, called PABA-Glu, and use it to make new folate in a pathway discovered by our co-author Jacalyn Green. We found that PABA-Glu is present in folic acid preparations including tablets bought from our local Boots. The circuitous route of folic acid breakdown, followed by resynthesis in bacteria and then uptake by the worm, does work to prevent folate deficiency, but we also find it has the negative effect of reversing the extended lifespan resulting from low folate bacteria.

In this paper, we show that [in C. elegans] folic acid requires a route through E. coli

Does this route exist in humans? The breakdown product is present in supplements, and intact folic acid probably breaks down further in the stomach, but we don’t know how much PABA-Glu comes into contact with bacteria. Much of it may get absorbed or metabolized before it reaches bacteria further down the gastrointestinal tract. Further experiments are needed.

If folic acid is absorbed by our gut bacteria, is it safe? We propose that there are situations such as in chronic diseases associated with overgrowth of pathogens, where an increase in bacterial folate status may have negative effects, but further investigation is needed.

In many countries such as the US and Canada, folic acid is added to flour. In other countries it is added to margarine, cereals and other foodstuffs. Mandatory fortification prevents many neural tube birth defects because mothers need sufficient levels of folate before they even know they are pregnant. However, some question whether it is safe and/or ethical to give folic acid to an entire population when not everyone needs it.

An increase in bacterial folate status may have negative effects [in humans], but further investigation is needed

There have been some studies suggesting that folic acid can have negative effects on health such as increasing risk of colon cancer, or masking vitamin B12 deficiency, but reviews of the literature by government-sponsored panels of experts have concluded that folic acid fortification is safe. We were surprised to see that these reviews have not considered gut microbes or folic acid stability. We hope that our paper will encourage more research in this area and that public health bodies take notice.

David Weinkove

Latest posts by David Weinkove (see all)

- Folic acid supplements and gut bacteria - 15th June 2018

Comments