We currently live in a world full of unpredictable challenges, whether they be in the form of the drug resistant microbes and emerging infectious diseases that threaten our health, or the global impacts of climate change. Amongst so much uncertainty one trend however is clear: we’re getting older.

In fact, our world is aging at a rate never before seen and for the first time in history most people can now expect to live beyond their 60th birthday. By 2050 it’s predicted that the world will be home to 2 billion people above that age (hopefully, I’ll be one of them), around 900 million more than today. For those of you hoping to reach 80 and beyond, you’ll be in good company as it’s thought that within just a few decades there will be as many octogenarians in China alone as are alive today, worldwide. Even within just 5 years there will be fewer children under the age of 5 than there are adults over 60.

You get the point, the world’s getting older, and quickly.

The challenge of population aging

Population aging is a transforming demographic force whichever way you look at it. As people live longer and populations age, a stark shift in global disease epidemiology is expected: in the near future the global loss of good health and life will be greater from noncommunicable or chronic diseases, such as dementia and cancer, than from parasites and infection. Ensuring that both our health and social systems are equipped for this shift is a significant and pressing challenge.

Why do we age?

Not a simple question to answer. At a basic biological level, aging can be attributed to the accumulation over time of compounding and varied molecular and cellular ‘damage’. Our bodies and minds are vulnerable to this process and as we get older the functional capacity of our biological systems deteriorates, leading to declining physical and mental health and a growing risk of disease.

Although the pace of population aging is much faster than ever before, there’s little evidence to suggest that end of life health has improved at anywhere near the same rate. Sadly, few older people today are able to enjoy their later years in better health than their parents could.

Reframing the debate

Unless challenged, many of us, including myself, don’t seem to question the ‘inevitability’ of age related decline, disease and disability: it’s just part of getting older (or so the story goes). There’s no doubt that the scientific community will continue to make amazing progress in understanding and treating diseases often considered ‘endpoints’ for the elderly, but perhaps a new approach is needed.

Although our chronological ages are immutable, more researchers than ever are now questioning whether the aging process itself can be modulated. Whilst getting older is inevitable, perhaps disease and disability don’t have to be.

A new precedent

A prominent group of researchers already plan on testing this theory in a clinical trial called Targeting Aging with Metformin, or TAME for those of you who like catchy acronyms. They plan on giving Metformin, a tried and tested medication used to treat type 2 diabetes, to a large cohort of people already affected by (or at risk of) 3 age related conditions – cancer, cognitive impairment or heart disease. Success for the trial would come in the form of any forestalling of disease onset, potentially setting an FDA approved precedent that aging is a medically treatable disorder. Which would be no small thing.

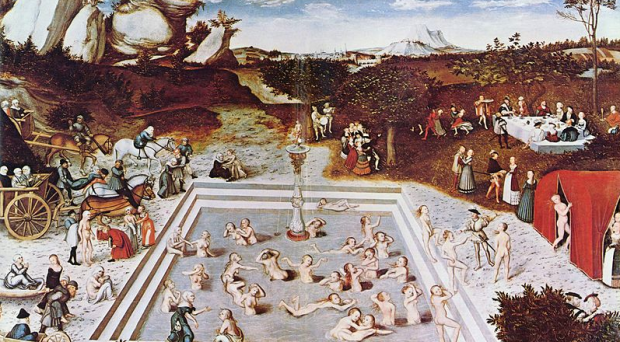

Before you rush out to buy some new swimwear on your way to the fountain of youth, I should say that those behind TAME aren’t claiming to be on a quest for immortality. If successful however the trial may point to new ways of increasing ‘health span’, as even modest reductions in the pace of aging will potentially confer significant benefits to quality of life.

If viewed as a malleable biological function, rather than an inescapable decline, it’s difficult not to think that aging should be placed at the center of public health research. After all, it’s the only condition guaranteed to affect every person on the planet.

So what if we do find ways to modulate the aging process, what happens next? Let’s hope we all live long enough to find out.

Thomas Appleyard

Latest posts by Thomas Appleyard (see all)

- The role of APOE4 during the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease. A Q&A with Professor Guojun Bu - 15th November 2016

- Evolution and cancer: A mathematical biology approach II - 23rd August 2016

- Quiz: Test your (action) potential! - 14th March 2016

Comments