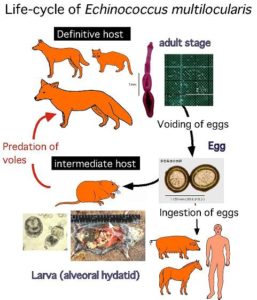

Vegetables, fresh fruit and mushrooms represent a potential source of infection by a variety of pathogens including the tapeworms, Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis. The sexually reproducing forms of both of these worms use various canines as their hosts. Unlike the typical image of a tapeworm, these are only a few centimetres long. Large numbers of them live in the gut and shed eggs that are voided with the faeces and thus contaminate the environment.

People can be infected if they accidentally ingest eggs, either by intimate contact with an infected canine (most usually dogs, so don’t let them kiss you) or via contaminated fresh produced, grown in areas where infected canines may defecate.

In both cases eggs hatch in the gut, but the resultant larvae do not live there. They enter the blood stream and invade tissues, usually the liver, and form large cysts where they reproduce asexually forming hundreds of a larval form called protoscoleces which will develop into an adult tapeworm if eaten by a carnivore

For both tapeworms, a sylvatic life cycle exists whereby wild ruminants or domestic sheep, goats or camels usually act as the secondary host for E. granulosus and small rodents for E. multilocularis.

The life cycle only continues when raw or undercooked, infected, flesh is eaten by another canine. Humans are thus a dead-end host for this zoonosis.

Pathology

Humans infected with E. granulosus suffer from human cystic echinococcosis: each worm produces a single fluid filled cyst that, after several years, can become football sized.

E. multilocularis causes alveolar cystic echinococcosis (AE) in which multiple small cysts are formed that spread throughout the internal organs. The disease progresses slowly and can be asymptomatic for as long as 15 years, but eventually produces disorders similar to liver cancer. It is extremely pathogenic with a fatality rate reaching over 50%.

Domestic dogs are the major source of infection in many parts of the world, see for example a recent paper on infection patterns in China, but in some parts of Europe the red fox represents a potential source of infection.

A study in Poland

In 2015 a study, conducted by Anna Lass and colleagues, focussed on Varmia-Masuria Province, Poland. Here the prevalence of E. multilocularis in foxes is as high as 50% and the area has the highest number of cases of AE in Poland. The transmission routes of this tapeworm were unknown.

One hundred and three samples of fruits (various berries) vegetables and mushrooms were collected from kitchen gardens, forests and plantations and analysed for the presence of E. multilocularis DNA.

Initial work, performed by artificial contamination of purchased fruit and vegetables suggested that many eggs were lost during preparation for DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing, as their previous work showed they could detect the presence of a single isolated egg.

Nevertheless, when their protocol was used with samples collected from the wild, the tapeworm DNA was detected in 23.3% of samples from gardens, forests and plantations. The highest proportion of contaminated samples being those collected from kitchen gardens.

Interestingly the authors noted a large increase in the fox population had been occurring in Varmia-Masuria Province at that time and people living there often consumed their own home grown fruit and vegetables and also collected fruits and mushrooms from the forest. They concluded that consumption of fresh fruits, vegetables and mushrooms could pose a risk of infection by this highly pathogenic tapeworm.

Findings challenged

Their findings have recently been challenged by Lucy Robertson and colleagues. These researchers recognise that Poland has a relatively higher incidence of AE than other Baltic countries. However, they propose that the inferences with respect to the danger posed by eating fresh, raw produce from the area that were made in the 2015 paper may have been too dramatic and cause undue concern.

They based their criticism on a number of points, including;

- They questioned why more of the Polish population were not infected, given the high incidence of egg contamination.

- They queried the contamination of raspberries as these grow off the ground and are unlikely to be contaminated with fox excrement.

- The presence of eggs in samples from plantations and from forests was questioned as the grassland rodents present in plantations are not good hosts for E. multilocularis.

- Finally, as fox density and fox infection levels vary considerably throughout the year they felt a breakdown of the sample material into collection periods should have been provided and they questioned the viability of eggs over time.

The reply

The authors of the original paper have just published a reply to this challenge.

- They point out that their study took place in an area where the incidence of AE was much higher than other provinces (in 1990–2011 it was 0.20 per 100,000 inhabitants, as compared with 0.014 in the entire country); as is the incidence of fox infection. Most AE patients in Poland are from rural areas and have contact with forests areas. In addition, a similar situation has been reported in Lithuania. They suggest humans are poor hosts for E. multilocularis and many exposures to eggs do not result in infection and they also suspect a high level of underreporting and misdiagnosis of AE. Thus infection incidence might indeed reflect the levels of food contamination that they found.

- They defended their sampling methods and point out their use of control material bought from supermarkets. Only low-growing raspberries were collected.

- Fruits and mushrooms were only sampled from the edge of forests, where fox faeces were found. Positive DNA samples were found in clusters suggesting foci of infection and, importantly, sampling sites were not selected randomly but on the basis of local knowledge about fox behaviour. This information was not included in their original study and would have helped to evaluate their findings.

- In terms of variations throughout the year, DNA samples were only collected between June and September when the fruits and mushrooms were available, not throughout the year.

Increased public awareness

The authors do not think the results of their study surprising as they were sampling sites with the highest risk of contamination. They reaffirm that although the risk of infection is unknown, public awareness of this risk of contracting AE in these areas should be increased and eating unwashed fruit and vegetables should be avoided.

Clearly there was no intention of scaremongering with respect to eating Polish fresh fruit and vegetables on the author’s part. As with all parasitological research, a fine line must be drawn between dissemination of information and the induction of panic.

Comments