Yellow Fever outbreaks are ongoing in Angola, with exported cases to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, and China. According to a recent situation report released by the World Health Organization, over 4,000 suspected cases and hundreds of deaths have been reported, mostly from Angola. The epidemic started in December 2015 and despite extensive vaccination efforts, there is ongoing transmission in the Angolan capital of Luanda- a foci of the current outbreak.

Yellow fever virus (YFV) is a species of flavivirus, meaning it is related to Zika virus, dengue virus, West Nile virus and several other viruses that are known to cause human outbreaks. These viruses are transmitted through the bite of an infected arthropod (usually a mosquito or tick species) and can infect not only humans, but an array of mammal and other animal species. Yellow fever’s name comes from the jaundiced (yellow) appearance that infected humans get– this is accompanied by fever, shivers, and headache. If the infection advances to a second, more serious, stage there is a 50% chance of death without treatment. There is no cure for yellow fever, but treatments that address the symptoms, such as rehydration, can improve patient outcomes.

Yellow fever virus is not a new public health threat. For centuries, yellow fever caused massive mortality in port cities when the vector and infected humans migrated to suitable regions. The virus originated in Africa, but was brought to the Americas 300-400 years ago along with the slave trade.

As one example, the Panama Canal was delayed due to Yellow Fever and malaria outbreaks – over 20,000 workers died from these diseases, and the completion was only possible due to massive investment in mosquito control to curb transmission and reduce morbidity and mortality. This was achieved by spraying oil into ponds and water-filled trenches to destroy breeding habitats of mosquitoes.

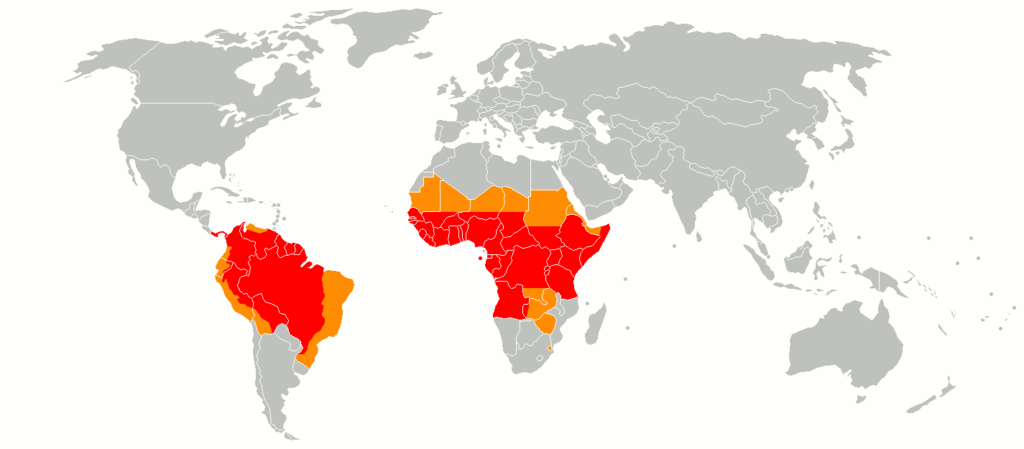

The virus is now endemic in many countries in South America and Africa. The distribution is largely determined by the presence and range of suitable vectors- it can be transmitted by several Aedes and Haemagogus species, and the urban Aedes aegypti is particularly suitable for maintaining human cycles. While Aedes mosquitoes are present in Asia, the absence of Yellow Fever in Asian countries is thought to be related to lower introduction rates during the peak of the slave trade.

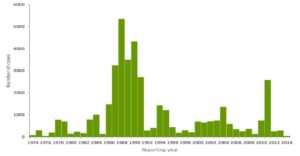

Yellow fever virus is maintained in sylvatic cycles and sporadically emerges in human populations. The last large epidemic of Yellow Fever was in 1986, when an outbreak in Nigeria infected an estimated 116,000 and killed 24,000 people.

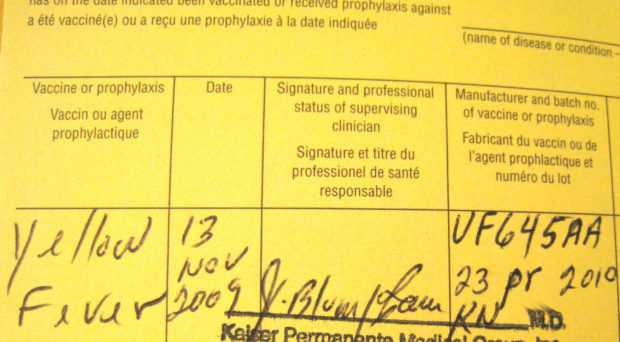

Vaccination against yellow fever provides life-long immunity to infection. The vaccines are relatively cheap ($2) and can be administered to most people over 9 months of age. However around 80% of the population must be vaccinated to provide herd immunity and reduce the likelihood of outbreaks.

Unfortunately, in many endemic regions, vaccination rates are low. Although there has been a fast response, vaccination campaigns in Angola will face the inevitable issue of supply – it’s estimated that only 80 million vaccines are made annually, and this recent epidemic is quickly using up these doses. The World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) has been reviewing evidence for using 1/5 of the normal dose. This strategy, known as fractional dosing, does not guarantee lifelong protection but would protect from yellow fever for at least 12 months and allow scaling up of the number of individuals vaccinated in emergency situations.

However, even though 8 million people have been vaccinated in Angola, there is still persistent transmission. This may be because population density is so high in urban areas where transmission is occurring. Infrastructure has a hard time keeping up with this rapid migration to cities, and poor sanitation and weak public services exacerbates the conditions creating an ideal environment for YFV transmission. Aedes mosquitoes often breed in closed containers, which can be found in areas where there is little access to drinking water and where there is poor sanitation. Mosquitoes are happy to breed in leftover garbage that accumulates rain water and receptacles used for storing drinking water.

Currently, an additional seven countries (Brazil, Chad, Colombia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Peru and Uganda) are reporting yellow fever cases that are not related to Angola. While the Angolan outbreak has led to some exported cases, particularly to neighbouring DRC, these other countries have developing outbreaks that warrant surveillance. Another outbreak on the scale of Angola could lead to more deaths due to vaccine supplies running low.

At this time, the outbreaks are viewed as critical national public health issues, but are not believed to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) . Priorities should be increasing vaccination, vector control, and case management in areas where transmission persists. Migrant workers and travellers in affected regions should also be vaccinated to prevent spread of the virus. Countries and areas with strong travel links to affected countries and with a local vector, such as China, should implement outbreak preparedness by improving surveillance and stockpiling emergency vaccinations.

Comments