Dengue is a viral disease endemic in tropical and subtropical regions, transmitted by the bite of mosquito vectors (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus). The World Health Organisation estimates that 50 million new cases occur worldwide every year. While the infection is typically associated with febrile symptoms, joint and muscle pain and headaches, the severe form of the disease (dengue haemorrhagic fever) is usually fatal, unless properly treated. The global incidence of dengue has increased significantly in the last few decades and this has been attributed to various factors including global travel, population growth, urbanisation and climate change. Dengue is currently considered the most prevalent human arboviral disease worldwide.

- Pictures of the two Aedes species able to transmit dengue virus. Left Aedes aegypti and right Aedes albopictus. Source Wikipedia. Copyright holders: Muhammad Mahdi Karim and James Gathany/CDC, respectively.

With the debate on the adverse effects of climate change on human health ever so heated, the prevalence and distribution of vector-borne diseases has taken centre stage. This has been reflected in the increasing number of publications around this topic. Climate change can be expected to impact transmission dynamics through its effect on mosquito reproduction and feeding habits, virus multiplication and human behaviour. Therefore, it is not surprising, though it is definitely striking, that two papers focusing on the effect of climate change on dengue fever in Europe have been published within the same week in two respectable peer-reviewed journals: The Lancet Infectious Diseases and BMC Public Health. This has been further strengthened by the report on the same day of publication of a new autochthonous (endemically transmitted) dengue case in the Var region of France which was accompanied by high level of press and media interest. While this timing in certainly coincidental, the reporting of several indigenous dengue cases in Europe provides clear evidence that the concern of the scientific community is legitimate.

The review paper in Lancet Infectious Diseases focused on the WHO European region (which is wider than the area commonly known as Europe). They have cited historical and recent dengue outbreaks in the region and highlighted that up until the 1930s, dengue was endemic in Europe. Thereafter, dengue has not been reported in Europe until 2010 (excluding an outbreak in Turkey and Israel in 1945). Undoubtedly, the 1935 “International Convention for Mutual Protection Against Dengue Fever” has successfully contributed to eliminate the mosquito vector “Aedes aegypti” that was established in the area.

For a long time, dengue has been considered an imported disease in Europe, with the infection being detected only in travellers returning from endemic areas. According to the ECDC, 1143 dengue cases were detected in 2010, constituting the second largest cause of hospitalisation in travellers after malaria. Since the establishment of Aedes albopictus in several European countries, entomologists and public health experts expressed concerns about the implication of this presence on the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases, especially dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever. This is particularly relevant considering the increasing global mobility of populations worldwide. However, these alarm bells fell on deaf ears, mainly because of the perception that these diseases are tropical diseases occurring in countries far far away. However, the fitness of parasites and vectors triumphed once more and reports of local transmission having been reported in 2010, 2013, and 2014 from mainland Europe, clearly demonstrating the vectorial capacity of the established vector (Aedes albopictus) and the danger associated with viremic returning travellers. Additionally, a sizeable outbreak caused by Aedes aegypti has been reported in Madeira, which highlights the risk of introduction of this highly competent vector into mainland Europe.

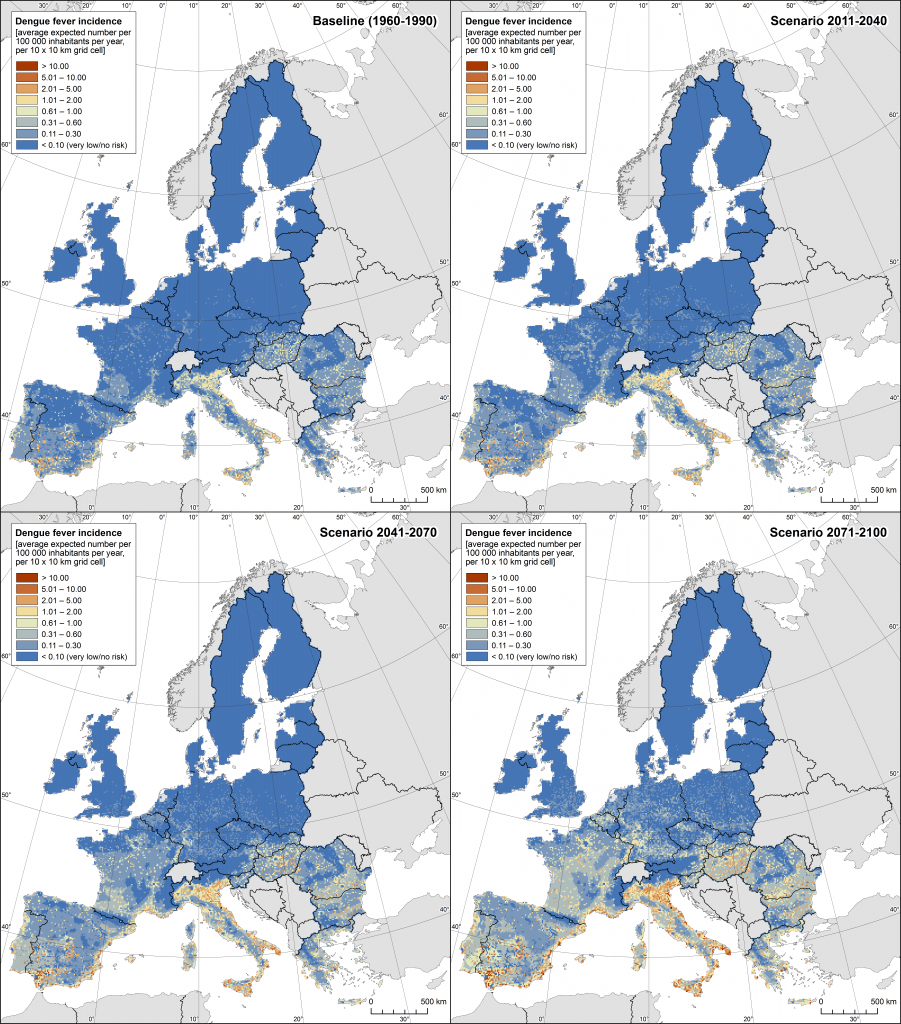

Numerous papers have modelled dengue risk at global, regional and local scales, most of which were based on vector presence. Some of these studies investigated the effect of climate change scenarios on future distribution of dengue and other investigators have already compared the strengths and weakness of methodological approaches used in these studies. Surprisingly though, no dengue risk map based on actual disease occurrence existed for Europe, as most risk maps were based on vector presence and/or were derived from dengue global risk maps. In our paper in BMC public health we attempted to fill this gap and estimate dengue risk in Europe under baseline conditions and climate change scenarios based on clinical data and accounting for various climatic and socioeconomic variables using fine scale projections. Our study found that climate change is likely to increase dengue risk in Europe especially towards the end of the century and that dengue hot spots are projected to be clustered around the Mediterranean and Adriatic coasts and in the Po Valley in northern Italy.

- Dengue fever incidence rate expressed as number of cases per 100 000 inhabitants per year for baseline conditions and climate change scenarios for early, medium and late century. From Bouzid et al., 2014. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-781

These two papers came to the shared conclusion that currently Europe is at low risk of dengue transmission. Nevertheless, this risk is real as highlighted by the increasing (though still limited) number of autochthonous cases. Europe is not alone in this situation and other developing countries are facing the challenge of dengue re-emergence after many disease free decades. Two such examples are USA and Japan. Since the establishment of Aedes albopictus, most European countries have active up to date Vector Surveillance Network. Additionally, some countries (at increased risk) adopted disease specific national plans incorporating integrated vector control and syndromic surveillance. France has a national prevention plan for dengue and chikungunya, which was immediately implemented when the autochthonous case was detected in August 2014. Control measures were restricted to the immediate vicinity of the case and involved insecticide spraying, removal of larval breeding sites and active clinical surveillance. An important factor for disease control is rising awareness of the general public, this is particularly relevant for vector-borne diseases. Therefore, bite avoidance campaigns have been an integrated part of control measures and the topic was the focus of the World Health Day 2014 “small bite, big threat: preventing vector-borne diseases”. Mosquito control remains the main intervention for dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases, however, it needs to be sustainable and evidence based. While still awaiting a vaccine, biological control for dengue had shown a great promise such as the release of Wolbachia infected Aedes that would limit dengue transmission. In conclusion, concerted and integrated control plans are needed to mitigate the increased risk of dengue in Europe.

Comments