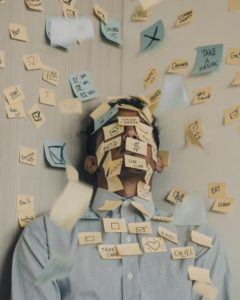

Many of us find it increasingly difficult to separate our work from our personal lives. Modern technologies exacerbate the problem, with our inability to ‘switch off’ and tendency to take calls and check emails outside of working hours. What’s more, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a new challenge for those of us working from home, where the line between our jobs and family lives has become even more blurred, and for those working longer shifts in hospitals, supermarkets or elsewhere.

It is already known that work-life imbalances can negatively affect both our physical and mental health. However, we know little about the factors that strengthen or weaken this association. New research published in BMC Public Health looks at the influence of gender and level of welfare provision by the state on the link between work-life balance and health.

In their study, Mensah and Adjei analyze data from over 32,000 workers, aged 16 to 64, from 30 European countries. This data was collected as part of the 6th European Working Conditions Survey, carried out in 2015 by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound).

The authors perform statistical analysis on the association between work-life balance and self-reported health, which previous studies have found to be a reliable proxy of overall health, and factor in other variables such as gender and welfare regime. Validating earlier studies, the results show that there is a significant association between work-life balance and health.

Gender differences in the association between work-life conflict and health

Traditional gender roles permeate our everyday levels such that, in many cultures, women more often take on a caring role within the family unit and men are seen as the so-called ‘breadwinner’. This is changing, with the last 40 years seeing increased participation of women in the labor market and a rise in the number of dual-earning families.

There is generally a stronger association between poor work-life balance and poor health among women.

How, then, does gender affect the association between work-life conflict and self-reported health? Mensah and Adjei find that while men more often report a poor work-life balance across different European countries, there is generally a stronger association between poor work-life balance and poor health among women.

There may be a number of reasons for this. Women still bear the greater burden of childcare responsibilities, for example, creating additional pressures at home as well as in the workplace. Women also face increased discrimination at work and lower rates of pay, both of which may contribute to the impact of work-life conflict on health.

The role of the welfare state

The strength of this study’s large cross-European sample is that it enables comparison between groups of countries with different welfare regimes, with countries classified as Nordic (Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway), Conservative (such as Germany and Switzerland), Liberal (UK and Ireland), Southern Europe (such as Greece, Spain and Italy) and Central and Eastern Europe (including Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Croatia and others).

The strength of this study’s large cross-European sample is that it enables comparison between groups of countries with different welfare regimes, with countries classified as Nordic (Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway), Conservative (such as Germany and Switzerland), Liberal (UK and Ireland), Southern Europe (such as Greece, Spain and Italy) and Central and Eastern Europe (including Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Croatia and others).

Mensah and Adjei report that work-life balance is best for both working men and women in the Nordic countries. There is also a weaker association between poor work-life balance and poor self-reported health in these countries, which the authors attribute to their substantial welfare provision including availability of childcare, universal healthcare and long parental leave.

The association between work-life conflict and poor health is strongest in countries with Liberal and Conservative welfare regimes, with Conservative states also being the only ones where the association is stronger in men than in women.

Multiple factors may be at play here, including increased emphasis on the male breadwinner role, weaker employment regulation and unions, and more stringent social welfare than the Nordic states. However, it remains to be established why Southern European states, with the least generous welfare policies, fared better. Further work is also needed to determine the specific contribution of individual policies on work-life conflict and health.

Striking a healthy balance in future

On a personal level, the findings of this study may help us to reflect on how often we allow commitments at work encroach on our personal lives and negatively impact our health. So how might we guard against the stresses and strains of work-life conflict in future?

The Mental Health Foundation, a UK charity, recommends a number of measures including better prioritization of tasks at work, taking proper breaks in the working day, dedicating time for exercise or hobbies, and keeping a record of time spent working or thinking about work.

The differential impact of working practices, employment law and welfare policies on women and men’s health must be considered.

The study also points to systemic differences to be addressed by governments and policymakers. As we strive towards equality, the differential impact of working practices, employment law and welfare policies on women and men’s health must be considered.

Of course, countries vary widely in political and economic landscape and so too does the level of social and financial intervention by the state, but strategies to help minimize work-life conflict would surely pay dividends in fostering a healthier population and workforce.

Comments