Loneliness is not a twenty first century creation. Nor is it the result of the physical distancing, self-isolation and distant and remote social relationships we are experiencing as a result of COVID-19. Like joy or sorrow, loneliness can be seen as part of being human. It has been described and experienced by people of different ages, across different cultures and in different historical periods.

What is loneliness?

Loneliness is the feeling or response we have when our social relationships fail to match our expectations or desires. This could be because the quality of the relations is superficial or lacking in the depth and meaning we would like. It can also be because the number of our relationships is lower than we would like. Loneliness may also result when how we experience our relationships, in person, on-line or by telephone, does not match our expectations. This is especially relevant during the distant and remote socializing we are experiencing during COVID-19. On-line or telephone conversations may combat loneliness by enabling us to keep in touch with our family and friends. Alternatively, these types of contact may make us feel lonelier by reminding us how much we miss personal contact. Loneliness is not the same as living alone, spending time alone or being socially isolated.

Why does loneliness matter?

Loneliness was once seen as a problem that was only experienced by older people. Indeed it was often seen as part of the normal ageing process. Now it is clear that loneliness effects people of all ages. This is important because being lonely is now seen as so serious that is seen as a public health problem. We now have a Minister for Loneliness and national strategies to combat loneliness. Much of the drive to tackle loneliness is because research has associated it with a range of health problems. These include death, chronic physical health problems such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, depression and mental health as well as health behaviors such as decreased physical activity.

Loneliness is increasingly being defined as a medical or health care problem rather than one of wellbeing and quality of life

Loneliness is increasingly being defined as a medical or health care problem rather than one of wellbeing and quality of life. We know that those people who experience loneliness reported lower levels of wellbeing, quality of life and life satisfaction. In the flurry of activity focused on the health problems associated with loneliness the links with wellbeing are overlooked. However these are very important and are why I would argue that loneliness really matters. All of us, regardless of age, evaluate our wellbeing and quality of life and this can be reduced by loneliness. For this reason alone, we need to understand loneliness and what factors can make people vulnerable to experiencing loneliness. This is especially important for older adults where national and international policies focus on living well in later life and of having a ‘good old age’. These policy goals mean that we need to understand the drivers of loneliness in later life if we are going to develop robust ways of addressing loneliness and support a meaningful and good quality of life for our older citizens.

What types of factors are related to loneliness?

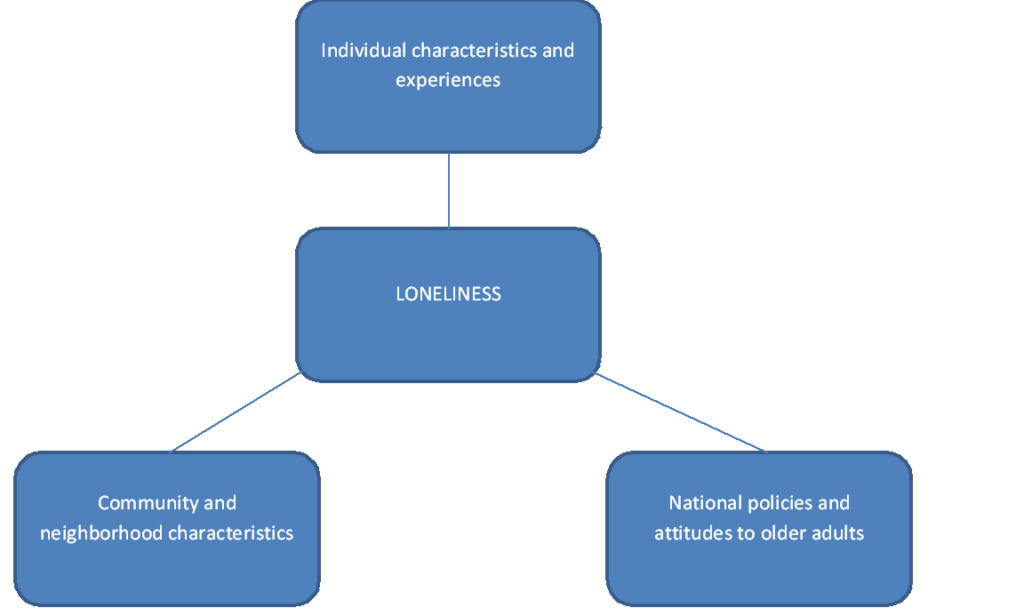

There are three different types of factors that may make older people vulnerable to loneliness. First there are individual characteristics such as widowhood or bereavement, low income or poor health. Secondly there are community and neighborhood factors such as the availability of parks or availability of facilities such as libraries. Thirdly there can be national or societal level factors such as policies and attitudes to older people. We know very little about how community or neighborhood factors are linked to loneliness. In our study we looked at two area characteristics – the index of multiple deprivation and area type (urban or rural). We studied their relationship with two measures of loneliness for 4,663 adults aged 50 and over who took part in the 2014 wave of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA).

There are three different types of factors that may make older people vulnerable to loneliness. First there are individual characteristics such as widowhood or bereavement, low income or poor health. Secondly there are community and neighborhood factors such as the availability of parks or availability of facilities such as libraries. Thirdly there can be national or societal level factors such as policies and attitudes to older people. We know very little about how community or neighborhood factors are linked to loneliness. In our study we looked at two area characteristics – the index of multiple deprivation and area type (urban or rural). We studied their relationship with two measures of loneliness for 4,663 adults aged 50 and over who took part in the 2014 wave of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA).

Identifying lonely places

Overall, 18% of participants reported that they experienced loneliness and 25% that they often felt lonely in the area where they lived. It is important to remember that just over two thirds of participants, 68%, did not report either form of loneliness. We found no difference for either measure of loneliness between participants living in urban and rural areas. There was no relationship between individual loneliness and the deprivation score for the community where participants resided. There a significant statistical relationship between the level of deprivation of an area and levels of area based loneliness. Those living in the most deprived communities were 53% more likely to report experiencing loneliness in the area than those living in the least deprived areas.

Those living in the most deprived communities were 53% more likely to report experiencing loneliness in the area than those living in the least deprived areas.

Integrating area and place of residence in loneliness research

Existing evidence investigating the factors that make older people, and other age groups, vulnerable to loneliness have focused upon individual characteristics such as marital status or household size. We also have evidence linking loneliness to transitions or changes in circumstances such as retirement, bereavement, becoming a carer or the onset of chronic illness. We have extended our understanding of loneliness by demonstrating a link with deprivation and now need to identify the components of deprivation-housing stock, lack of community facilities, transport, availability of blue-green spaces or lack of community cohesion and trust that are creating lonely places.

Comments