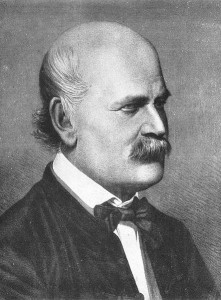

Today is the 195th anniversary of the birth of Ignaz Semmelweis and BMC Infectious Diseases is celebrating the achievements of this pioneer of infection control.

At the beginning of the 19th century people were unaware that bacteria could cause disease and it was not until the work of scientists, including Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, in the second half of the century that the causative agents of many common diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis were identified.

In 1846 Semmelweis was working as a doctor in the First Obstetrical Clinic of Vienna General Hospital. He was troubled by the rate of puerperal fever in the hospital and the resulting high maternal mortality rate. In addition he was intrigued by noticeable differences in the rates of this disease between the two obstetric clinics at the hospital.

The First clinic, where Semmelweis worked, provided teaching services for medical students; many of whom came directly to patients from anatomy classes in the hospital morgue. The Second clinic was designated for midwife training and had a much lower rate of puerperal fever. According to Semmelweis’ later account this was such common knowledge that women begged for admission to the Second clinic and often preferred to give birth outside of the hospital than risk treatment in the First clinic.

The death of Jakob Kolletschka in 1847 provided a clue to explain the differing rates of infection between the two clinics. Kolletschka was a fellow doctor at Vienna General Hospital and had suffered an accidental cut by a medical student’s scalpel during an autopsy. He subsequently died after developing an infection that was very similar to that of the women suffering puerperal fever. Semmelweis noted the similarities and concluded that something brought from the autopsy room to the clinic was causing the disease.

Following this revelation, he instigated a policy where doctors had to wash their hands in a chlorine solution between the autopsy room and the ward, and later expanded this to include treatment of equipment used on patients. As a result, the infection– and the subsequent mortality rate– in First clinic dropped significantly and was soon comparable with that of the Second clinic.

Semmelweis tried to publicize his findings but many of his contemporaries were highly critical and refused to listen. In 1861 he published ‘Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever’ which detailed his findings, but it was poorly received.

Sadly, Semmelweis’ life was cut short in 1865 after his death during admission to an asylum but as knowledge of bacterial disease and transmission increased, his contribution to infection control has become widely recognized.

Hospitals today now understand the importance of hand hygiene and disinfection to prevent the spread of infections. Researchers now study factors such as the durability of gloves, adherence to hand washing protocols and whether to screen healthcare workers to determine the best way of preventing the spread of hospital acquired infections. However, we cannot overlook the importance of Semmelweis’ seminal study and we shouldn’t forget how so something so simple can make such a big difference.

Comments