The CONSORT guideline for reporting randomized trials has received widespread attention from the scientific community in the 20 years since it first appeared. It has been cited over 12,000 times across all iterations and publications (it has been updated twice and published simultaneously across multiple journals).

We recently updated a study quantifying the level of support across top impact factor biomedical journals… These journals tend to show their support by “endorsing” the use of CONSORT by authors trying to publish trials.

Journals have been the most prominent supporters of CONSORT. We recently updated a study quantifying the level of support across top impact factor biomedical journals, which was published today in Trials.

These journals tend to show their support by “endorsing” the use of CONSORT by authors trying to publish trials.

However the wording of endorsing statements is varied, ranging from strong statements instructing authors to submit a “completed” checklist and flow diagram, to less clear indications, sometimes simply referring authors to the CONSORT website and providing no other guidance on what is expected.

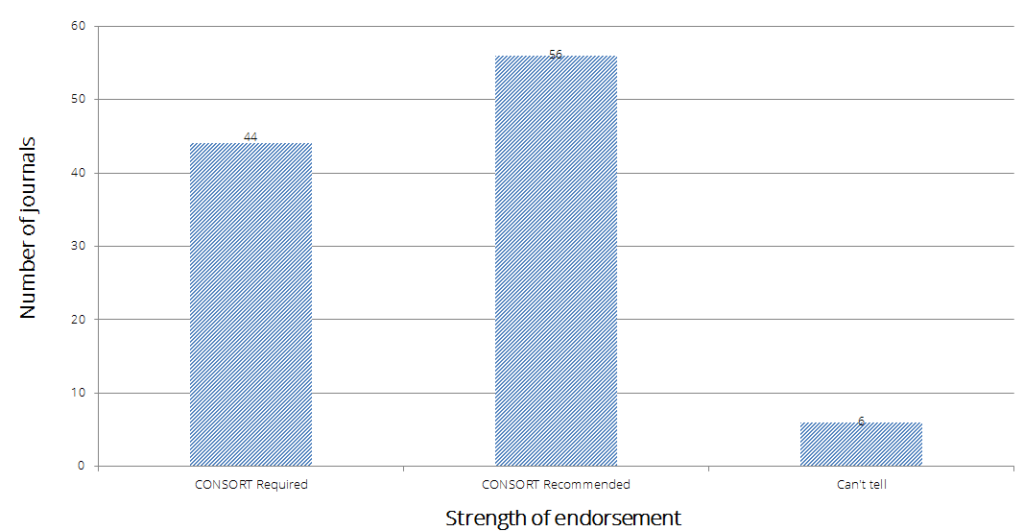

Over an 11 year period, the number of top impact journals endorsing CONSORT has grown from 22% (36/166) in 2003 to 63% (106/168) in 2014 (figure below).

One might expect that more trials are being better reported due to such endorsement, and indeed, we have seen such an association. However, it is apparent that, even among endorsing journals, major reporting problems persist.

One might expect that more trials are being better reported due to such endorsement, and indeed, we have seen such an association. However, it is apparent that, even among endorsing journals, major reporting problems persist.

So, who is to blame for non-adherence to CONSORT and poor reporting?

One group of researchers thinks the responsibility lies largely with the journals that publish the trials.

The COMPare Project, led by Ben Goldacre and colleagues, has examined the occurrence undisclosed selective reporting of outcomes among trials published in the 5 highest impact general medical journals (NEJM, JAMA, The Lancet, Annals of Internal Medicine, The BMJ) through October 2015 to January 2016. All of these journals have been endorsers of CONSORT since at least 2004.

In 2010, after the accrual of evidence of the problem, the CONSORT group included in the most recent CONSORT checklist (CONSORT 2010) a clear statement about reporting all pre-specified outcomes (item 6a in the checklist) and reporting any changes to such outcomes from the protocol (item 6b in checklist).

After comparing published trials to their protocols or trial registry entries, the COMPare team found alarming numbers of undisclosed outcome switching (upgrading, downgrading, adding, or removing) between what was planned and what was reported (only 9 of 67 trials were free of selective reporting).

After comparing published trials to their protocols or trial registry entries, the COMPare team found alarming numbers of undisclosed outcome switching…

When they fed their findings back to the journals, reminding them of their CONSORT endorsement and trial registration policies, and requested that corrections be made, each journal reacted differently.

Some journals did not acknowledge that the discrepancies were real or problematic, some eventually made policy changes towards better transparency, and others issued corrections and published the COMPare criticisms as requested.

The study findings and full text of these communications were made public on the COMPare website: https://compare-trials.org/.

The New England Journal of Medicine, the highest impact factor journal in general medicine, is one journal that has denied that the identified outcome switching is problematic and has opted to not issue corrections to any trials.

In their response to the COMPare team about their CONSORT endorsement they state the following:

“The New England Journal of Medicine finds some aspects of CONSORT useful but we do not, and never have, required authors to comply with CONSORT.”

It is clear from reading the CONSORT guidelines, that CONSORT Group intends the guideline as a minimum set of items to be included in a trial report, to be addressed in their entirety rather than a set of items from which to pick and choose.

As an FYI, currently, the NEJM’s statement about CONSORT in their Instructions to Authors reads,

“In manuscripts that report on randomized clinical trials, authors may provide a flow diagram in CONSORT format and all of the information required by the CONSORT checklist. When restrictions on length prevent the inclusion of some of this information in the manuscript, it may be provided in a separate document submitted with the manuscript. The CONSORT statement, checklist, and flow diagram are available on the CONSORT website.”

In 2004, when the journal first endorsed CONSORT, the word “should” was used in all instances the word “may” occurs above. It is unclear when the change was made.

For those journals making public statements endorsing CONSORT, it is clear that these statements do not always translate into completely, transparently reported research.

So what is to be concluded?

For those journals making public statements endorsing CONSORT, it is clear that these statements do not always translate into completely, transparently reported research.

In order for this to be achieved, journals must not only be clear on what authors should do, but also adhere to their own recommendations and policies around transparent reporting. Checking for compliance with the recommendations in CONSORT before a trial is published should be a regular, scheduled activity during peer review or somewhere in the editorial process. A recent BioMed Central blog describes the piloting of an automated tool that will do just that.

Comments